The Future of Move at Aptos

by Wolfgang Grieskamp

Move is a novel smart contract language used by several blockchains including the Aptos Network. Move was designed for the Libra/Diem Blockchains at Meta based on security-first principles, which makes it arguably the safest language for smart contracts on the market. At the same time, this approach led to a minimalistic language, leaving out many advanced language features that ease the life of the developer. At Aptos Labs, we are developing a new compiler for Move, the Aptos Move Compiler, which comes with a set of new language features to fill in the gaps in the original Move language design, all without compromising security. In this article, we outline some of the most important upcoming features. Many of these features are not fully finalized: we are sharing this early preview to solicit feedback from the community as we begin to implement them.

· Receiver Style Function Calls

· First Class Higher Order Functions

· User Defined Abilities

· Resource Access Control

· Returning Global References

· Enum Types and Public Structs

· Specification Language

· Additional Features

· Timeline and Process

Receiver Style Function Calls

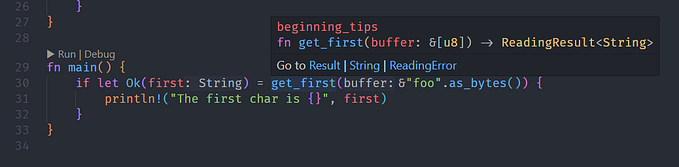

Receiver style function call syntax is the well-known notation where a target (the ‘self’) of a call is separated from the function name and remaining arguments, as in receiver.func(args). This notation can be seen as a syntactic alternative for func(receiver, args). However, there is a bit more to the added convenience of this notation:

- The function

funcdoes not need to be imported explicitly or qualified by the defining module, since the type of the receiver, the first argument, determines it. - If the receiver parameter to

funcis a reference, the compiler can automatically create this reference. For example,func(&mut receiver, args)is written in receiver style just asreceiver.func(args).

The Aptos Move compiler will implement this notation. It is enabled by using a particular naming convention for the first (receiver) parameter of a regular function definition, as seen below:

fun length<E>(self: &vector<E>)Here, self is not a keyword, but an indication to the compiler that this function is allowed to be called as vec.length(). Notice that this does not forbid the current notation length(&vec) which is still supported, allowing to upgrade existing code to the new notation without a breaking change.

With the presence of receiver style, restricted overloading of function declarations is allowed, as long as they are distinguished by the type of the receiver parameter. Henceforth, the following declarations are allowed in a module:

fun name(self: &T): String { self.name }

fun name(self: &R): String { self.other_name }First Class Higher Order Functions

One feature Aptos added in early 2023 to Move is the limited support for higher-order functions and lambdas. For example, Move now supports the following notation, which checks whether a vector contains an element with value greater zero (note that we assume receiver style, as discussed above):

vec.contains(|elem| elem > 0)However, the current support for higher-order functions is limited: only inline functions can take functions as parameters, and only lambda expressions can be passed to those function parameters. A serious restriction of inline functions is that they do not work across module encapsulation boundaries, potentially tempting builders to sacrifice modular encapsulation. Moreover, using too many inline functions leads to an increase in code size, hitting the limits of transaction payload size when deploying code.

The Aptos Move compiler will support general higher-order functions, and the Move VM will be extended to support them as well. Practically, no syntax changes will happen, but higher-order functions will no longer be restricted to just inline functions. For example, we can write code like below (not possible today with inline functions because of private field access):

struct State { val: u64 }

public fun transform(self: &mut State, f: |u64|u64) {

s.val = f(s.val)

}There are two challenges with this new feature:

- Reentrancy: general higher-order functions open the problem of reentrancy attacks. We have a solution to this problem via Resource Access Control, as discussed later.

- Closures and References: a closure is the construct which captures context variables which a lambda references. For example, in

let x = …; contains(vec, |elem| elem > x),xis such a context variable. This capturing becomes difficult if references need to be captured. The solution to this problem is to only allow closures which capture references to be passed downwards on the call stack. This ensures that the lifetime of the closure is enclosed by the lifetime of the captured references.

User Defined Abilities

Many programming languages have the concept of traits (i.e., bounded parametric polymorphism) which allows associating generic features with a type, for example, ordering for that type. Such polymorphism allows elegant code reuse, for example, writing code that works on any type with ordering. In Move, we already have the related concept of abilities. Those are restricted to a few predefined use cases, like the copy, key, store, and drop abilities. With the upcoming Aptos Move Compiler, we plan to extend the existing Move ability system to allow new abilities to be user defined in the language.

Abilities can be declared with a declaration as below, where we use an iterator ability as an example. For simplicity, the iterator we describing is consuming the elements it iterates via a simple API:

ability Iterator<E> {

fun has_more(self: &Self): bool;

fun next(self: &mut Self): E;

}Given such an ability, one can implement generic algorithms that work on any type that has this ability, for instance, searching an iteration for a matching element:

fun any<E, I: Iterator<E>>(iter: &mut I, predicate: |&E|bool): bool) {

while (iter.has_more()) {

if (predicate(&iter.next()) return true;

}

false

}In the above code, I: Iterator<E> implies the polymorphic constraint that I is bound to only those types that have this ability.

Abilities can be implemented with declarations as below:

fun <E>Iterator<E>::has_more(self: &vector<E>): bool { !v.is_empty() }

fun <E>Iterator<E>::next(self: &mut vector<E>): E { self.pop().unwrap() }We can also derive abilities from each other:

fun <E, I1: Iterator<E>, I2: Iterator<E>>

Iterator<E>::next(self: &mut Chain<I1, I2>): E

{

if (self.first().has_more())

self.first_mut().next()

else

self.second_mut().next()

}Some more details:

- Implementation source: an ability can be declared as public or not. Both abilities are visible anywhere. However, a public ability can be implemented for types defined anywhere, even in other packages, while a regular ability only in the same package where the type lives (orphan rule). Note that the availability of public ability is experimental and may help to have more flexibility for evolving cross-contract standards. For comparison, it is not available in Rust (but it is f.i. in Go).

- Implementation uniqueness: there can be only one unique implementation of an ability for a given type in any execution context. This implementation must be provided by a single module — perhaps outside of the type’s package. Both requirements are checked at module loading time. This means, even if the type checker may not discover it because of separate deployment units, ambiguous implementations can never coincide or be overwritten somehow in a given execution context. This property avoids semantic confusion of abilities, as well as protects against malicious attacks via abilities.

- Dynamic dispatch: abilities as described so far do not enable dynamic dispatch, but are resolved statically at compile time. Compared with Rust, this is the difference between the

dyn Ttype declaration and a regularTtype declaration. We are still discussing whether dynamic dispatch should be supported for abilities. If so, protection against reentrancy would work similar as with higher-order functions via resource access control.

Resource Access Control

Resource access control (AIP-56) allows Move code to explicitly constraint the set of resources which a function or transaction can access. While this feature has applications in the domain of blockchain execution and security, it also enables various scenarios on the language level, so we will quickly describe it here.

Access control specifiers are a generalization of the existing acquires declaration in Move. Instead of just fun f(..) acquires R where R is some resource type (a struct with key ability), one can distinguish reads R and writes R. Moreover, it is possible to use wildcards and negation. For example, reads 0x42::* grants read access to all resources declared at the given address, and !writes 0x42::* rejects all write access to resources at this address. For more details, see AIP-56.

One important difference between access specifiers and acquires-annotations is that the former are globally visible part of a function type and can reference resources outside of the current module. Moreover, access specifiers are dynamically evaluated, allowing them to be applied to code which has not mentioned them: executing a function with a particular access restriction will pass on this restriction to all code called from that function.

Access specifiers provide a solution for safe calls into unknown code across trust boundaries — those calls can happen as a result of higher-order functions or user defined abilities. For example, consider a public function which takes a function parameter. Via the function type, we can ensure that any concrete parameter does not make unwanted resource accesses:

module myaddress::m {

public fun do_some_work(…, callback: |u64| !write myaddress::*) …

}In the above declaration, we require the callback function parameter to not write any resources declared at the same address as the given module, preventing reentrancy attacks via the callback.

Returning Global References

Currently, Move does not support returning a reference to global storage from a regular function call. For example, we cannot write the following code:

fun access_resource(a: address): &Resource {

abort_if_access_invalid(a);

borrow_global<Resource>(a) // reference safety error here

}With the introduction of inline functions, it became possible to write functions as above, but those can be only used in the module where the resource type is defined. This restriction makes it harder to specifically write framework code. For instance, for Aptos Objects, it would be natural to provide accessors to objects via functions returning references, instead of having to leave it to user code to resolve addresses to references.

The reason for this restriction is that in current Move, the origin of a returned reference cannot be declared. However, we can use resource access specifiers as an indicator to derive the relation of returned references to global storage:

fun access_resource(a: address): &Resource

reads Resource

{

borrow_global<Resource>(a) // ok because of access declaration

}More precisely, the rules for this interpretation are as follows:

- A returned reference which cannot be borrowed from the type of any input reference is considered a global reference.

- Every global reference must have a matching unique access specifier for a resource type from which the reference type can be borrowed.

With this information, an extended reference safety analysis can maintain all required memory safety conditions of Move. At Aptos Labs, we are in the process of formalizing and implementing this new analysis.

Notice that this heuristic extends the already existing one to deal with returned references. Currently, any output reference is considered to be borrowed from any input reference. The extended handling described here deals with the cases where this rule cannot be applied. Whether the heuristic is enough has to be seen. Technically, it is not a big step from here to lifetime-label annotations, as found in Rust, but, while sound, those can be difficult to use, so we try to avoid them for now in the Move language.

Enum Types and Public Structs

Enum types as found in the Rust language are a powerful feature to define variations of data. For the new Aptos Move compiler, we plan to add full support of enums. Enum declarations will look as below:

public enum Option<A> has copy, drop, store {

None,

Some(A)

}A matching expression similar to Rust will allow discrimination of enums:

match option {

None => 0,

Some(x) => x + 1

}As seen in the above declaration, the public modifier is used with the enum type. A public enum can be matched outside of the module it is defined in (otherwise, only local matching is allowed). The same public modifier will become available for regular structs, allowing them to be accessed outside of modules, and also passed as transaction parameters. Also note the introduction of positional fields in enums: those are allowed for structs as well (in turn, named fields are also allowed for enum variants).

With enum types, we will allow recursion in types, which is currently not allowed in Move. An enum type declaration with recursion must have at least one non-recursive, terminating variant, as in the declaration below:

public enum List<A> has copy, drop, store {

Nil,

Cons{ hd: A, tl: List<A> }

}One common application for enum types is resource versioning. For example, one can define a resource as below:

enum AccounData has key {

V1 { <some fields> },

V2 { <some fields>, <additional fields> }

... any future versions can go here ...

}This allows using the same storage slot for a new version of the resource. Applications like this require the handling of missing variants in a match. At compile time, the compiler will error on missing variants. However, at runtime the bytecode verifier allows those missing matches. Only when the match is executed and a variant cannot be handled, execution will abort. This allows adding variants to enums without preventing verification of older code which is already deployed.

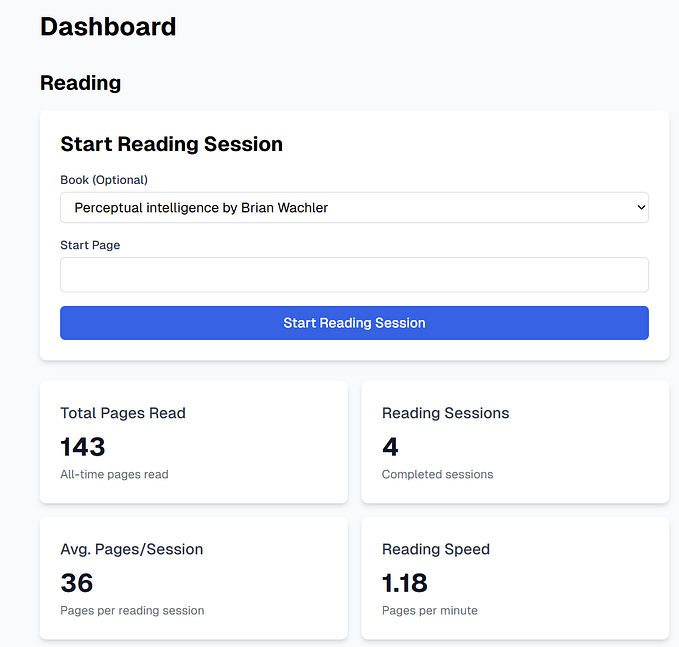

Specification Language

The introduction of general lambdas and higher-order functions is also helpful to tackle one of the major practical problems in specification and verification: dealing with loop invariants. With higher-order functions and abilities, one can avoid many loops, and instead use a filter-map-reduce pattern.

The prover can then use special decision procedures for filter-map-reduce instead of going into the complexity of loop invariants. A simple example is given below:

let sum = reduce(&vec, 0, |a, e| a + e)The prover can verify such expressions without further help, by combining knowledge of reduce and of the body of the lambda expression.

For more complex situations, the lambda expression syntax is extended to be able to attach pre- and post-conditions. For instance, below a more complex function is used for aggregation in a reduce expression. At the same time, a specification function exists which models this behavior, so we can specify this relation with a specification block associated with the lambda:

reduce(&vec, N,

|a, e|

spec { // Specifies result of lambda

ensures result == spec_aggregate(a, e);

}

aggregate(a, e)

)Additional Features

There are multiple smaller features which are planned to be added to Move, here is a list of some of them:

- Signed integer types (

i8, i16, i32, i64, i128, i256) - A type to represent an integer range, written as in

start..end - More intuitive syntax for indexing vectors (

v[index], v[start..end], &v[index], &mut v[index], and in types[T]instead ofvector<T>) - More intuitive syntax for

borrow_global<R>(addr)andborrow_global_mut<R>(addr)(aligned with vector indexing,R[addr],&R[addr]and&mut R[addr]) - A new syntax for loops:

for (var in exp) body.Here, exp can be an integer range, or anything which implements theIteratororIntoIteratorability.

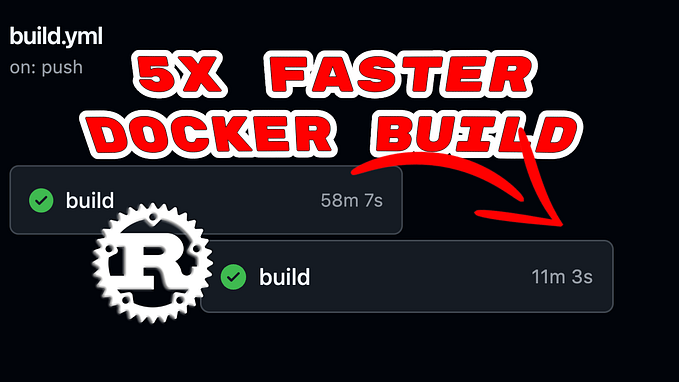

Timeline and Process

We expect to land most of those language extensions in the 1st half of ’24. The new Aptos Compiler will be in beta towards the end of ’23 with the primary goal of feature parity to the old one. New features will be added incrementally based on prioritization driven by our users — you — and by applications. We will solicit feedback on language features through Aptos Improvement Proposals (AIPs), which will allow the community to discuss and influence the design. There is a lot in store for Move at Aptos, and we are excited to push the language forward together with you to the next level!